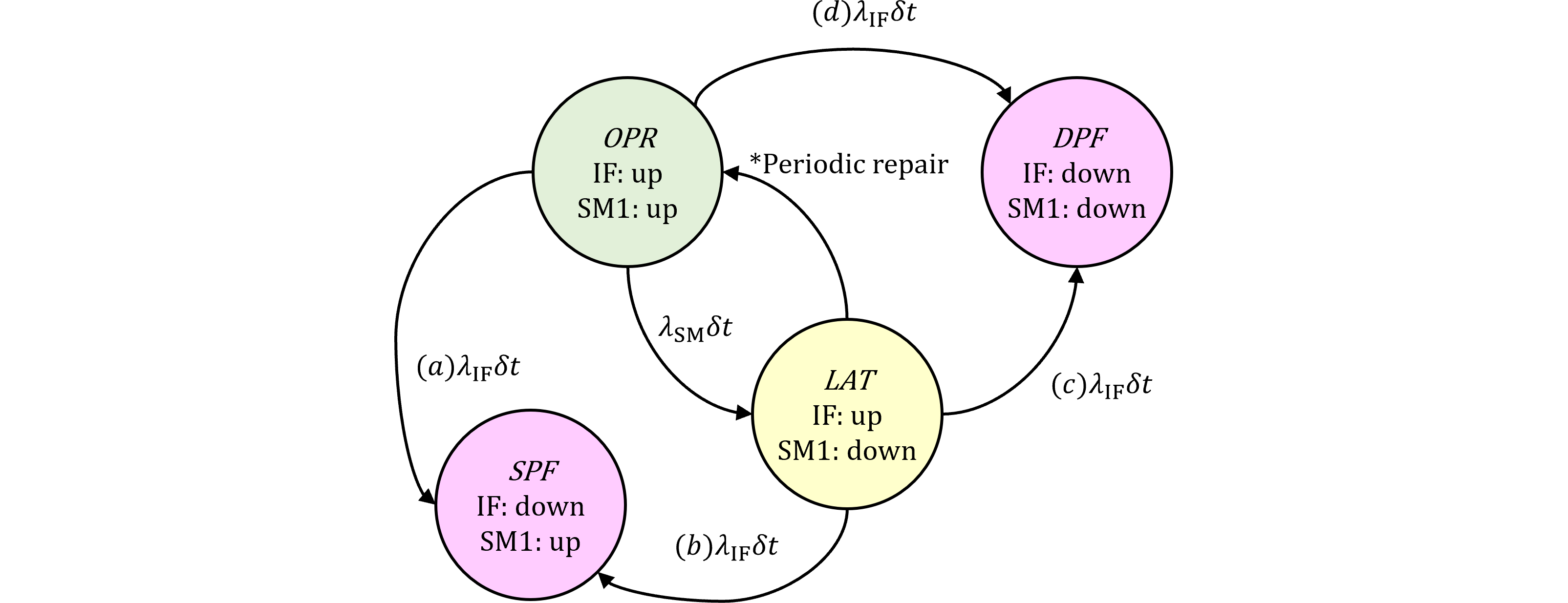

IFの状態確率は前記事の表、SMの状態確率は以前の表368.2に基づき、(a)~(c)まで場合分けして積分方程式を立てます。被積分関数は状態確率×遷移確率(微小確率)で表されます。遷移確率は条件付き確率です。この状態確率のうち

IF関連をグリーン、SM関連項をブルーで表します。また遷移確率をレッドで表します。この色分けは表の色分けとは関係ありません。

(a)からのSPF確率の時間平均は、IFが(2)、SMが(10)+(12)の条件から、

$$

\begin{eqnarray}

\overline{q_{\mathrm{SPF(a),IFU}}}&=&\frac{1}{T_\text{lifetime}}\Pr\{\mathrm{SPF\ via\ (a)\ at\ }T_\text{lifetime}\}\\

&=&\frac{1}{T_\text{lifetime}}\int_0^{T_\text{lifetime}}\Pr\{\mathrm{OPR_\overline{prev}\ at\ }t\cap\mathrm{IF\ down\ in\ }(t, t+dt]\}\\

&=&\frac{1}{T_\text{lifetime}}\int_0^{T_\text{lifetime}}\bbox[#ccffcc,2pt]{(1-K_\mathrm{IF,RF})R_\mathrm{IF}(t)}\bbox[#ccffff,2pt]{A_\mathrm{SM}(t)}\bbox[#ffcccc,2pt]{\lambda_\mathrm{IF}dt}\\

&\approx&(1-K_\mathrm{IF,RF})\lambda_\mathrm{IF}-(1-K_\mathrm{IF,RF})\alpha,\\

\text{ただし、}\\

\alpha&:=&\frac{1}{2}\lambda_\mathrm{IF}\lambda_\mathrm{SM}\left[(1-K_\mathrm{SM,MPF})T_\text{lifetime}+K_\mathrm{SM,MPF}\tau\right]

\end{eqnarray}

\tag{376.1}

$$

(b)からのSPF確率の時間平均は、IFが(2)、SMが(9)+(11)の条件から、

$$

\begin{eqnarray}

\overline{q_{\mathrm{SPF(b),IFU}}}&=&\frac{1}{T_\text{lifetime}}\Pr\{\mathrm{SPF\ via\ (b)\ at\ }T_\text{lifetime}\}\\

&=&\frac{1}{T_\text{lifetime}}\int_0^{T_\text{lifetime}}\Pr\{\mathrm{LAT2_\overline{prev}\ at\ }t\cap\mathrm{IF\ down\ in\ }(t, t+dt]\}\\

&=&\frac{1}{T_\text{lifetime}}\int_0^{T_\text{lifetime}}\bbox[#ccffcc,2pt]{(1-K_\mathrm{IF,RF})R_\mathrm{IF}(t)}\bbox[#ccffff,2pt]{Q_\mathrm{SM}(t)}\bbox[#ffcccc,2pt]{\lambda_\mathrm{IF}dt}\\

&\approx&(1-K_{\text{IF,RF}})\alpha,\\

ただし、\\

\alpha&:=&\frac{1}{2}\lambda_{\mathrm{IF}}\lambda_{\mathrm{SM}}\left[(1-K_{\mathrm{SM,MPF}})T_\text{lifetime}+K_{\mathrm{SM,MPF}}\tau\right]

\end{eqnarray}

\tag{376.2}

$$

(c)からのDPF確率の時間平均は、IFが(4)+(6)+(8)、SMが(9)+(11)の条件から、

$$

\begin{eqnarray}

\overline{q_{\mathrm{DPF(c),IFR}}}&=&\frac{1}{T_\text{lifetime}}\Pr\{\mathrm{DPF\ via\ (c)\ at\ }T_\text{lifetime}\}\\

&=&\frac{1}{T_\text{lifetime}}\int_0^{T_\text{lifetime}}\Pr\{\mathrm{LAT2_\text{prev}\ at\ }t\cap\mathrm{IF\ down\ in\ }(t, t+dt]\}\\

&=&\frac{1}{T_\text{lifetime}}\int_0^{T_\text{lifetime}}\bbox[#ccffcc,2pt]{K_\mathrm{IF,RF}\left[K_\text{IF,MPF}\color{red}{K_\text{IF,det}}R_\mathrm{IF}(t)+\color{red}{(1-K_\text{IF,det})}A_\mathrm{IF}(t)\right]}\\

& &\qquad\qquad\cdot\bbox[#ccffff,2pt]{Q_\mathrm{SM}(t)}\bbox[#ffcccc,2pt]{\lambda_\mathrm{IF}dt}\\

&\approx&K_{\text{IF,RF}}\color{red}{K_\text{IF,det}}\alpha+K_{\text{IF,RF}}\color{red}{(1-K_\text{IF,det})}\beta,\\

ただし、\\

\alpha&:=&\frac{1}{2}\lambda_{\mathrm{IF}}\lambda_{\mathrm{SM}}\left[(1-K_{\mathrm{SM,MPF}})T_\text{lifetime}+K_{\mathrm{SM,MPF}}\tau\right],\\

\beta&:=&\frac{1}{2}\lambda_\mathrm{IF}\lambda_\mathrm{SM}\left[(1-K_\mathrm{MPF})T_\text{lifetime}+K_\mathrm{MPF}\tau\right],\\

K_\mathrm{MPF}&:=&K_\mathrm{IF,MPF}+K_\mathrm{SM,MPF}-K_\mathrm{IF,MPF}K_\mathrm{SM,MPF}

\end{eqnarray}

\tag{376.3}

$$

(d)からのDPF確率の時間平均は、IFが(3)+(5)+(7)、SMが(10)+(12)の条件から、

$$

\begin{eqnarray}

\overline{q_{\mathrm{DPF(d),IFR}}}&=&\frac{1}{T_\text{lifetime}}\Pr\{\mathrm{DPF\ via\ (d)\ at\ }T_\text{lifetime}\}\\

&=&\frac{1}{T_\text{lifetime}}\int_0^{T_\text{lifetime}}\Pr\{\mathrm{LAT1\ at\ }t\cap\mathrm{SM\ down\ in\ }(t, t+dt]\}\\

&=&\frac{1}{T_\text{lifetime}}\int_0^{T_\text{lifetime}}\bbox[#ccffcc,2pt]{K_\mathrm{IF,RF}\left[K_\text{IF,MPF}\color{red}{K_\text{IF,det}}F_\mathrm{IF}(t)+\color{red}{(1-K_\text{IF,det})}Q_\mathrm{IF}(t)\right]}\\

& &\qquad\qquad\cdot\bbox[#ccffff,2pt]{A_\mathrm{SM}(t)}\bbox[#ffcccc,2pt]{\lambda_\mathrm{IF}dt}\\

&\approx&K_{\text{IF,RF}}\color{red}{K_\text{IF,det}}\alpha+K_{\text{IF,RF}}\color{red}{(1-K_\text{IF,det})}\beta,\\

ただし、\\

\alpha&:=&\frac{1}{2}\lambda_{\mathrm{IF}}\lambda_{\mathrm{SM}}\left[(1-K_{\mathrm{SM,MPF}})T_\text{lifetime}+K_{\mathrm{SM,MPF}}\tau\right],\\

\beta&:=&\frac{1}{2}\lambda_\mathrm{IF}\lambda_\mathrm{SM}\left[(1-K_\mathrm{MPF})T_\text{lifetime}+K_\mathrm{MPF}\tau\right],\\

K_\mathrm{MPF}&:=&K_\mathrm{IF,MPF}+K_\mathrm{SM,MPF}-K_\mathrm{IF,MPF}K_\mathrm{SM,MPF}

\end{eqnarray}

\tag{376.4}

$$

追記:このまとめを記事#492に記述しました。

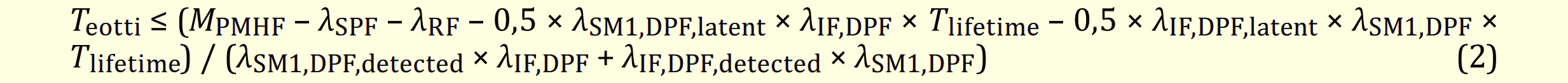

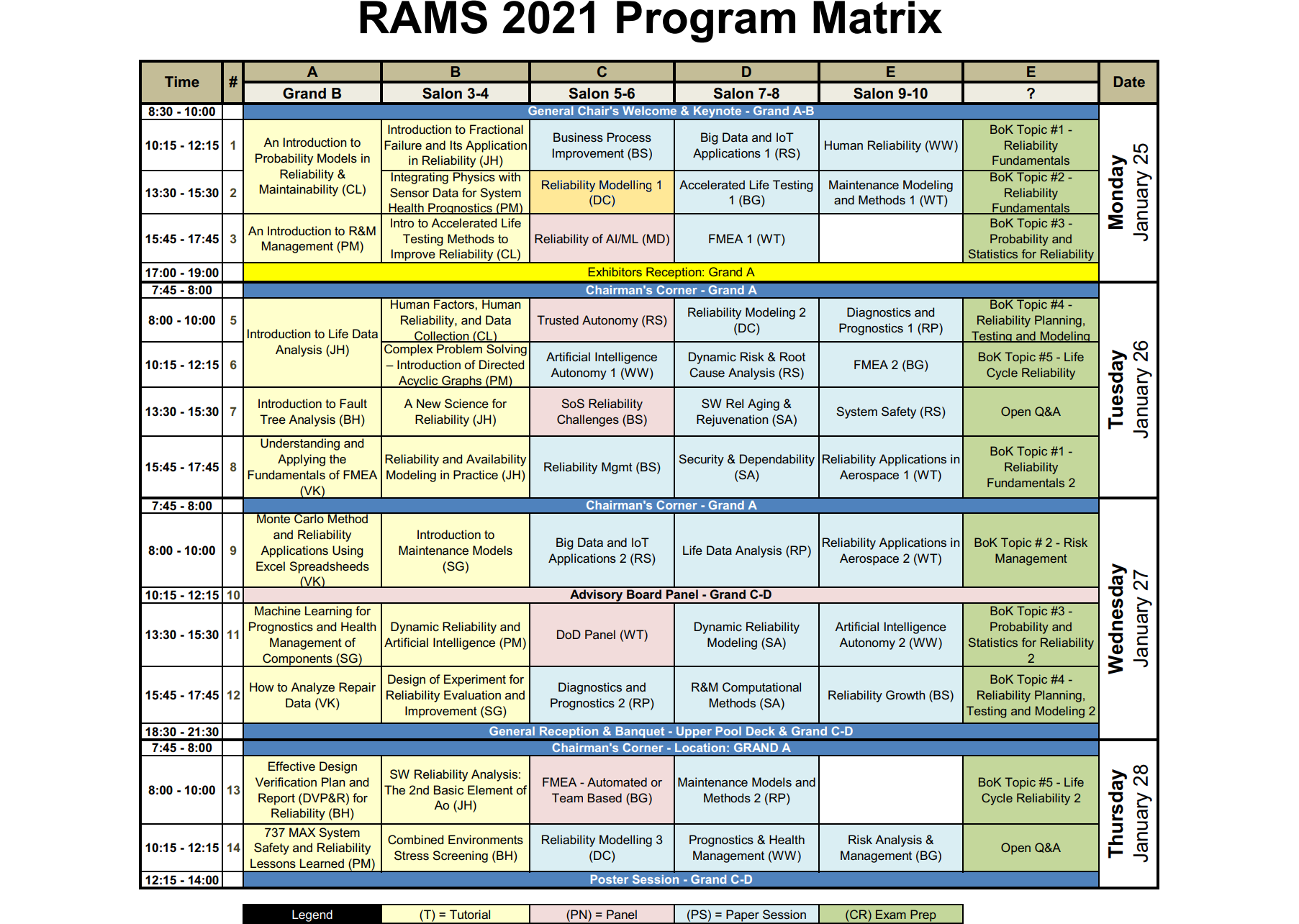

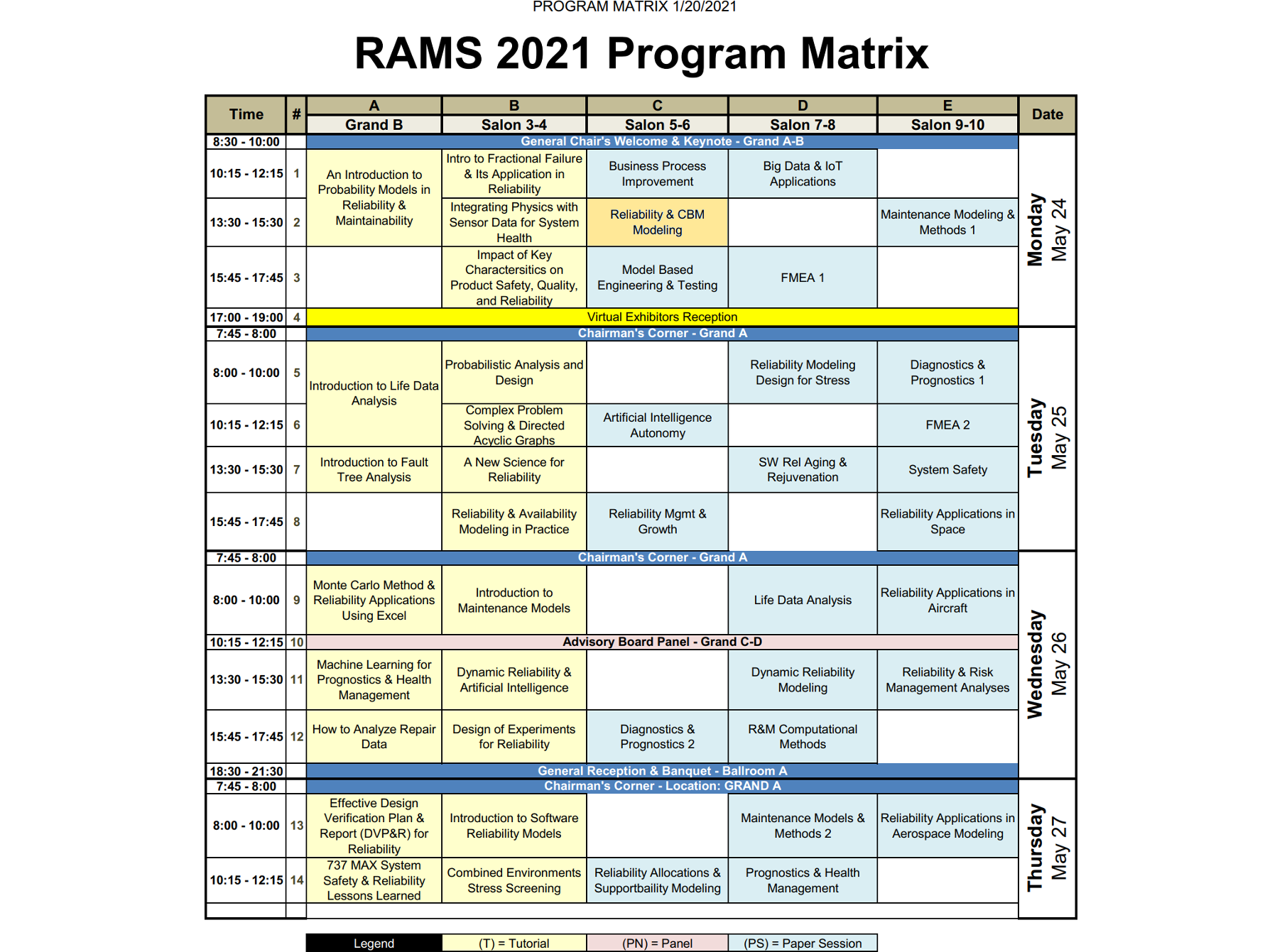

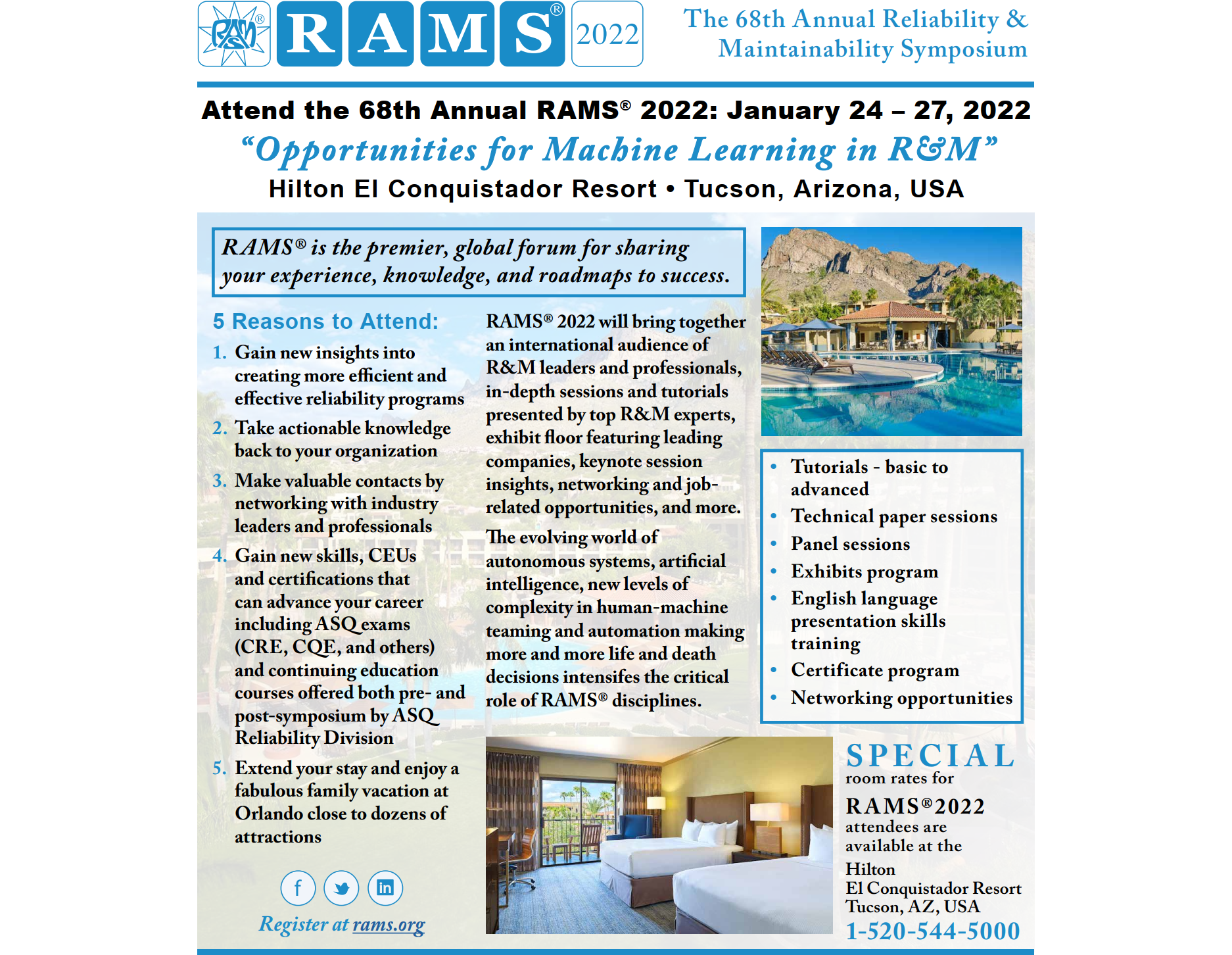

RAMS 2022においてMPF detectedの再考に基づくPMHF式の論文発表が終了したため、秘匿部分を開示します。

前のブログ

次のブログ

前のブログ

次のブログ