|

26 |

弊社代表 桜井 厚の論文がIEEE信頼性学会(RAMS)に3年連続採択 |

|

ISO 26262機能安全(注1)コンサルティングを提供するFSマイクロ株式会社(本社:名古屋市)代表取締役 桜井 厚の論文が、2021年10月26日、第68回RAMS 2022(注2)に採択されました。RAMS 2022は、2022年1月24日から27日まで米国アリゾナ州ツーソンにて開催予定の、IEEE(注3)信頼性部会主催の国際学会です。

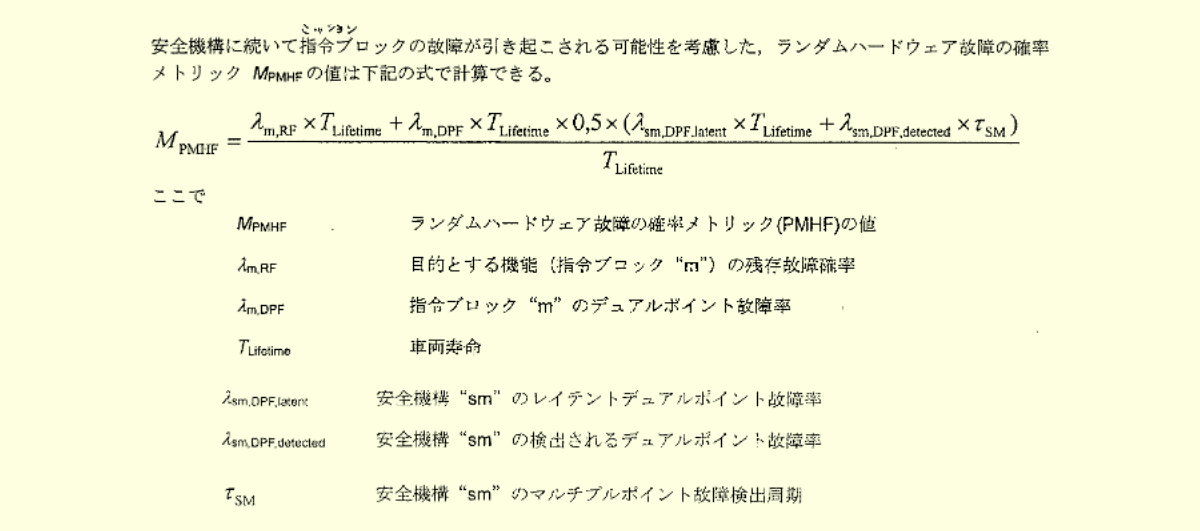

弊社代表 桜井 厚は2017年にIEEEの製品安全に関する国際学会である第14回ISPCE 2017(注4)において、最優秀論文賞を受賞しました。同著者の論文は2020年から3年連続でRAMSに採択されており、IEEE学会としては今回で4回目の採択となります。今回RAMS 2022で採択された論文は「Formulas of the Probabilistic Metric for Random Hardware Failures to Resolve a Dilemma in ISO 26262」と題し、ランダムハードウェア故障の確率的メトリクス(PMHF:注5)を正しく計算する数式を提案するものです。

2018年に発効したISO 26262第2版ではPMHF式が改訂されていますが、その数学的な定義が明確ではありませんでした。桜井 厚は2020年に第2版で曖昧だった点を明確にし、新たなPMHF式を導出しました。しかしながら、この式は規格第2版にも存在する、検出された多点フォールト(MPF:注6)をレイテントフォールト(LF:注7)とみなすという前提に基づいており、一方でその前提は、規格自身の規定するレイテントフォールトメトリック(LFM:注8)と矛盾します。

本論文はこの規格の矛盾を解消することを目的とし、検出されたMPFがLFにならないという前提の下に、新たなPMHF式を導出しました。この式によりPMHF値が正しく評価され、緊急操作許容時間間隔(EOTTI:注9)に関する設計制約が40倍軽減されることから、耐故障システム(注10)での設計工数の削減が期待されています。

【お問い合わせ先】

商号 FSマイクロ株式会社

代表者 桜井 厚

設立年月日 2013年8月21日

資本金 3,200万円

事業内容 ISO 26262車載電子機器の機能安全のコンサルティング及びセミナー

本店所在地 〒460-0011

愛知県名古屋市中区大須4-1-57

電話 052-263-3099

メールアドレス info@fs-micro.com

URL http://fs-micro.com/

【注釈】

注1:機能安全は、様々な安全方策を講じることにより、システムレベルでの安全性を高める考え方。ISO 26262は車載電気・電子機器を対象とする機能安全の国際規格

注2:RAMS(ラムズ)はThe Annual Reliability & Maintainability Symposiumの略。IEEE信頼性部会が毎年主催する、信頼性工学に関する国際学会 http://rams.org/

注3:IEEE(アイトリプルイー)はInstitute of Electrical and Electronics Engineersの略。電気工学・電子工学技術に関する、参加人数、参加国とも世界最大規模の学会 http://ieee.org/

注4:ISPCE(アイスパイス)はIEEE Symposium on Product Compliance Engineeringの略。IEEE製品安全部会が毎年主催する、製品安全に関する国際学会 http://2017.psessymposium.org/

注5:PMHF(ピーエムエイチエフ)はProbabilistic Metric for Random Hardware Failuresの略。車載電気・電子システムにおいて、車両寿命間にシステムが不稼働となる確率を時間平均した、ISO 26262におけるハードウェアに関する設計目標値のひとつ

注6:MPF(エムピーエフ)はMultiple-point Faultの略。 一点のフォールトでは安全目標を侵害せず、複数のフォールトの組み合わせにより安全目標侵害となるようなフォールト

注7:LF(エルエフ)はLatent Faultの略。潜在フォールトと訳される。MPFのうち、安全機構により検出されないフォールト

注8:LFM(エルエフエム)はLatent Fault Metricの略。LFがシステムにどれほどあり、そのどれほどが検出できるかのカバレージであり、ISO 26262におけるハードウェアに関する設計目標値のひとつ

注9:EOTTI(イーオーティーティーアイ)はEmergency Operation Tolerant Time Intervalの略。この期間内に修理するか代替処理に切り替えれば安全目標侵害が起こらない時間間隔

注10:耐故障システムは、故障した場合に直ちに機能を失うことなく、本来の機能を代替することができる安全性向上のためのシステム